Glimpses from the Chase February 15th, 2021

From Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches, A Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British, Indian, Colonial, and Foreign Sport with Thirty Two Full Page Illustrations Volume 10 1893, London; Mssrs. Fores Piccadilly W. 1893, All Rights Reserved.

GLIMPSES OF THE CHASE,

Ireland a Hundred Years Ago.

By ‘Triviator.’

FOX-HUNTING has, like Racing, Shooting, and even Dancing, had its phases and fashions ever since it became a National sport, and we may be pretty sure that though we of the guild and fraternity of fin desiecle fox-hunters make it our boast that as the ‘ heirs of all the ages ‘ we have brought the royal sport to the acme of perfection, every contemporary phase was the best adapted to the manners, customs, and requirements of the period ; and that, grotesque and absurd as some of the practices of our forbears appear to us now, many of our improvements and requirements and sublimations of sport would afford them in turn many a hearty laugh. After all, if sport be the desideratum, whatever makes for that end in the opinion of its votaries, must be deemed successful, and if real war—of which, according to Somerville and his pupil John Jorrocks, Fox-hunting is the image—was a comparatively innocuous affair in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, when contrasted with the deadly issues of modern scientific slaughter, it attained its aim as effectually as the present system, though more slowly and tentatively.

Indeed, in a few points, we have not improved upon an cestral form, as, for instance, in the sociable side of the chase, and the consequent camaraderie produced among fox-hunters. The Pytchley reunions, as we learn from the best statistics, now occasionally muster seven hundred mounted men and women, not to speak of the ‘mixed multitude’ who pursue on wheels, or the regiment of runners. Sociability would be impossible in such a crowd of all sorts and conditions of manhood and womanhood, where the preliminary parade has some features in common with Pall Mall and Piccadilly in the season, and so long as the canons of the chase are faithfully observed, no one is too particular as to ‘ who’s who,’ though all are supposed to have learnt ‘ what’s what.’ Indeed, so far as we can gather from the side lights of literature and the fine arts, sociability was the keynote of Fox-hunting towards the close of the last century and the commencement of the present. Shakespeare limns for us a chivalrous prince declaring on the eve of an international battle that—

‘ The man who this day sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother, be he ne’er so vile

This day shall gentle his condition.’

So in the great internecine struggle between the slavery and anti-slavery States of America, whenever the German soldiers who had espoused the Northern side met together in one of the provincial capitals, their challenge to their comrades on furlough was ever on these lines—’ You fight mit Siegel and you drink mit me,’ varied according to circumstance and commands. Similarly did our sociable sires insist that those who shared together the perils of pursuit and rejoiced in its raptures should hold sporting symposia together, and run their runs over again under the inspiring influences of Sneyd’s claret and potations of poteen that had never seen the gauger’s eye. Indeed, so backward and behindhand in means of inter-communication was the country, that it was absolutely necessary for the maintenance of the chase that hospitality should be as open-handed and universal as we now find it in some of our colonies, and we learn that to these sporting oases men were wont to come from long distances, and take the country as they found it, thinking more of the sociable side of the pastime, perhaps, than of the mere riding element ; otherwise it would be hard to imagine that sportsmen with due regard to their own necks, or their hunters’ knees, should have picked out such happy grounds for themselves as Brayhead, Killiney, and bits of Wicklow, but for the fact that a few sporting squires and noblemen cordially welcomed the devotees of Diana, and that Fox-hunting and good fellowship went hand in hand, a condition of things of which we get pleasant glimpses in the song of the Kilruddery Hunt, dedicated, we presume, to the Lord of Kilruddery, the Earl of Meath, otherwise a good part of the vicinity would seem to the fastidious foxhunter about as tempting as the Rocky Ridges of Cintra, near Lisbon, where the woods probably hold many foxes. Glimpses of this pleasant brotherhood of the chase might, nay, may still be seen at Wentworth-Woodhouse, the Yorkshire home of the Fitzwilliam family, where for a certain number of days absolutely open house is kept for the pilgrims of pursuit; and they might have been seen on even a larger scale at Thomastown, the residence of that hospitably minded squire, Mr. Matthews, who kept open house at his seat in Tipperary, and among the inducements for venatic visitors to come and taste his cheer, actually maintained three packs of hounds, namely, buckhounds, foxhounds, and harehounds, for his guests, mounting them besides if they had not brought their hunters with them. Of course such institutions could only be maintained where society was more or less of a close corporation, and when railways did not inject into all accessible meets hordes of hunting men and women, of whom nobody knew anything save that they affected in their well groomed persons ‘the properties’ of the chase, made up in most orthodox style and pattern.

In another respect we must give the palm to the arrangements of our ancestors, for their fields were very small and homogeneous, made up of sportsmen who were proud of the prowess of their hounds, and did not press the hounds unduly, or ride on top of them in the modern fashion. When Melton became, in the first half of the century, a Mecca for nomadic Nimrods, we hear through Parson Louth, the laureate of the Leicestershire pastures, that a favourite meet would bring out a couple of hundred cavaliers, more or less. Thus at Billesdon Coplow—

‘ Two hundred such sportsmen ne’er were seen at a burst,

Each resolv’d to be there, each resolv’d to be first.’

Happy the huntsman, now-a-days, who has only two hundred men and horses thundering in his wake ! Perhaps a score would have represented a large meet in the days we write of, a number ample for sociability, but comparatively harmless for mischief on days when scent was not supremely serving, as well as being more amenable to the Master’s directions.

It should also be placed to the credit of these sportsmen of the olden time that they were no Sybarites, and went through a great amount of what we might term hardship to compass their ends and aims. Many of us have read of the Cockney who had himself called at an unwontedly early hour, and reaching Euston Station, in his eagerness to be in time to catch the morning mail to Blisworth, where his hunters were located, got into a wrong carriage by mistake, and was so overcome by his exertions that he went fast asleep, and missed his train and his hunt, having been roused from his day dreams by a porter, whose duty it was to examine the carriages prior to their starting. In the days we write of there were no such luxurious and far-reaching covert-hacks as trains, and the distances cantering hacks covered would astonish pursuers of the present day, thirty miles being no unknown journey to a meet, while that meet was always fixed at an early hour, so that foxes might be found on the run before they had returned to their earth, after their noctivagous raids. And here we may refer to a favourite trysting place of the Ormonde and King’s County pack, one of the oldest hunting corporations in Ireland, and closely identified with the Rossmore family, namely, ‘ Nanny Moran’s Rock, at break of day.’

Now, anything more abhorrent to the taste and ideas of a Nimrod of the last decade of the nineteenth century than a long ride in the dark, to a gaunt rock, whose only merit was that it was planted in the heart of a fine, wild grass country, where wild OLD foxes abounded, can hardly be conceived, and we may be quite sure that if a modern M.F.H. encouraged such peep-o’-day pursuit, his subscriptions and his fields of followers would dwindle disastrously. At the commencement of the century, however, many were found not only willing but zealous to keep tryst and time there ; proving that ‘ The labour we delight in physicks pain ;’ and the hunting songs of the day refer to the indebtedness of sportsmen to the lady they called ‘ Luna,’ who favoured their early fox forays with her gracious beams, being, according to the mythology of Greece, none other than the Diana of the day, Patroness of pursuit, though at night she sometimes lent her light to ‘ the minions of the moon.’

In point of fact, these matitudinal musters of our forefathers were not unlike the cub-hunting fixtures of the present day, which are designed for the education of hounds and foxes alike, and which would lose to a great extent their raison d’etre, if they were more popular and fashionable. It is the substantive of the last adjective that is simply ‘ smothering’ sport in some parts of England, and that is compelling masters of hounds to resort to all sorts of strange devices and ruses, in the interests of their hounds and subscribers, such as foregoing the advertising of their fixtures in the public prints, and holding their rendezvous at unpleasantly ante-meridian hours. No difficulty of this kind ever presented itself at the commencement of the century in either England or Ireland, and, indeed, in the latter island it has never or only rarely been felt as yet, and the fields there are infinitely less ‘ mixed ‘ than in England, as every one knows every one, or something about him, or her, and sporting strangers are rarely seen in the field, and often a hundred is a good large field in any part of the Green Isle ; two is redundant, and extra numbers are considered bewildering, and rarely occur save occasionally at the Spring Sessions of the Ward Union Stag hounds, on a few Saturdays in Kildare, and when the Meath hounds make their venue within riding distance of Dublin. And in these cases the inconvenience does not last very long, for in addition to the absence of gates, dear to the dilletanti sportsmen, and the certainty of the proximate presence of a few formidable fences, the master of foxhounds invariably reduces the redundancy of riders by drawing away from towns and cities, and generally in the direction of the kennels, from which at starting he may be separated by an interval of thirty miles, a not infrequent occurrence in royal Meath. The rarity of railways, and the infrequency of trains, seems to point to the absence of any congestion of the chase for many years to come in the ‘ distressful country,’ and up to the present time there has been hardly any ground for a grumble, seeing that all sportsmen who come out to hunt have to contribute at least half-a-crown to the expenses of the pack, and fifteen or sixteen pounds (the take sometimes at a fashionable fixture) is a welcome ‘ rate in aid ‘ to the exchequer of the chase. When Ireland becomes really rich, as well as ‘ great, glorious and free,’ possibly hunting crowds will become a nuisance as in England ; but that Milesian millennium has not been even approached yet ; though the prophetic voice of Curran foretold its ultimate advent, for when a wealthy tobacconist of Dublin asked him for a legend to put under his newly acquired arms on the panel of his carriage, the witty Master of the Rolls suggested ‘ Quid rides ‘ (why do you laugh?), and the double entendre will suggest itself at once. Now ‘Quid’ rode in his chariot or phaeton, but no doubt ‘Quid’s’ son? would all hunt with ‘ the Wards,’ ‘ the Meaths,’ or the Kildares. And here let me state what I saw last season—a sporting railway contractor going by train to an opening meet of his favourite pack. He would not miss the function, but neither could he waste an early hour, so his secretary sat next him in the carriage and took down in short-hand the dictation of the railway king. How such a proceeding would have amazed old-time fox-hunters ! ‘ A deck of cards ‘ in a post-chaise they could well understand, but a series of letters ! Never! Indeed, if that jade Report speaks truly, some of the greatest of that fox-hunting fraternity were poor hands at either writing or dictating letters (if that time-saving process obtained then).

For instance, the great Giles Eyre—

‘ Who thought nothing at all

Of a six-foot wall.’

on hearing from a brother sportsman of a genius who could knock off twenty letters at a sitting, exclaimed, ‘Its all very well you’re telling me such a yarn, but show me the man.’ Yet no-doubt—

, The same Giles Eyrej

Would make him stare,

If he had him with the Blazers.’

The mention of that last pack, ‘ the Blazers ‘—so called probably because its members were eminent in the use of the saw-handled family-pistols, at a time when ‘ Did he blaze ? ‘ and ‘Will he blaze?’ were almost the first questions asked about a young man of position ‘debutting’ into society—puts me in mind of another phase of Foxhunting in ‘old Ireland ‘ (so called in contradistinction to modern or new Ireland), and that was its peripatetic nature, for if there was a fair, hostelry, or even a modest ‘ pub.’ in the centre of a hunting district, ‘ the Blazers ‘ would take it for a term, and scour the whole country round. I have seen one or two small cribs, many, many miles from the kennels, which they were said to occupy periodically. Sir Josiah Barrington tells us in his amusing way how a number of Queen’s County sportsmen occupied a small crib of this sort during a frost, having first put down a hogshead of claret, killed a bullock, procured musicians, and got a number of game cocks together. The first night when full—’ Veteris Bacchi pinguisque farina‘—they were laid out on the floor with their martial cloaks around them, but as their heads abutted on a newly plastered wall they became by morning fixtures; imbedded, or inheaded, in the wall, and had to be cut out of it ! ‘

Possibly the style of the chase in Ireland early in the century will be best illustrated by an account of ‘ a desperate foxchase,’ which was accounted worthy of a place in the Irish Racing Calendar of its year, a calendar which also contains records of cockfighting and the rules of cocking :—

‘ On the 4th of December last Colonel Eyre’s foxhounds had one of the most desperate runs ever recorded, of one hour and fifty minutes— desperate from its length, desperate from the pace kept up, and desperate from the dreadful storm that raged for nearly the last hour, and

in the very teeth of which Reynard ran; with the exception of one short check the chase was maintained with unabated fury all through. To choose a leap was to be thrown out. At half-past eight o’clock in the morning they drew over the Old Earth at Coolaghgoran for the spotted fox. Tony, the huntsman, knowing well his abilities from former runs, matched his chasehounds the day before, and fed them early. He calls this pack the light infantry, to distinguish them from the slow, heavy draft that were lately sent from England. I was on the Earth a little after eight ; ’twas rising ground, and as the dawn broke, ’twas cheery to behold the foxhunters, faithful to their hours, approaching from distant directions, and as they all closed to the point of destination, the pack ‘ in all its beauty’s pride ‘ appeared on the brow of the hill—

” Oh, what a charming scene :

When all around was gay, men, horses, dogs,

And in each cheerful countenance was seen,

Fresh blooming health and never fading joy.”

The taking his drag from the Earth was brilliant beyond common fortune, with a train which runs off in a blaze, they hardly touched it till they were out of sight. Madman, that unerring finder, proclaimed the joyful tidings, each foxhound gave credit to the welcome information, and they went away in a crash ; it was a perfect tumult in Mr. Newstead’s garden, there the villain was found, and we went off at his brush —

” Where are your disappointments, wrongs, vexations, sickness,

cares ?

All, all are fled, and with the panting winds lag far behind.”

‘ In skirting a small covert in the first mile we divided on a fresh fox; it was a moment of importance : nothing but prompt, vigorous, and general exertions could repair the misfortune : it was decisive, and we now faced the Commons of Carney ; broad and deep was the Bound’s drain, but what can stop foxhunters ? The line had been maintained by five couples of hounds; they crossed the road, and finding themselves on the extensive sod of the Common, they began to go ‘ the pace.’ A scene now presented itself which none but a foxhunter could appreciate, for its beauty was not discernible to the common and inexperienced eye. At this period the chase became a complete split ; the hounds, which had changed and had now from different directions gained the Commons, could not venture to run in on the five couple without decidedly losing ground, and to maintain it instinct directed them to run on credit, and flanking the five couple the whole pack formed a chain of upwards of 200 yards abreast across the Commons, but as the chain varied through the hollows and windings of this beautiful surface, the hounds on the wings in turns took up the line and maintained their stations, as the others had done, so well was this pack matched. Here we crossed walls that on common occasions would have been serious obstacles. The second huntsman on a young one, following Lord Rossmore, called out, ” What is on the other side, my Lord ? ” “I am, thank God,” was the answer. We now disappeared from the Commons of Carney, and at this time the pack was hunting so greedily that you would think every dog was hitting like an arrow. We now passed by Carrigagorm for the woods of Peterfield, in the teeth of the most desperate storm I ever witnessed of rain, hail, and wind. Distress was now evident in the Field, for notwithstanding the violence of the gale, ” the pace ” was maintained ; this was the most desperate part of the chase, and as the foxhounds approached the covert, I thought they had got wings : the rain beat violently, with difficulty we could hold our bridles, the boughs gave way to the storm. The Light Infantry were flying at him, and the crash was dreadful. The earths in Peterfield were open, but Reynard scorned the advantage, and gallantly broke amain. He now made for the River Shannon,

” Where will the chase lead us bewildered ” ?

Some object afterwards changed his direction, and away with him to Clapior. He crossed the great Drain of the Lough, and here we left young Burton Persse (” who had come all the way from Galloway to enjoy a regular cold bath.”) He went down tail foremost, and “no blame to him.” There was no time for ceremony, but Tony, who knew the depth of the Bath, took his leave of him, roaring out ” I’ll never see your sweet face again ” ” By—— ” says the Colonel, ” you were never more mistaken ; never saw him more regularly at home in my life. He’s used to these things, man ! ” And truth requires me to state that he joined us again, and before and after the Bath he rode in a capital place, and many a mile he ran and away by the old Castle of Arcrony, famous in the annals of hunting, and all over its beautiful grounds, and over the great Bound’s drain of Coolaghgoran again, for poor Reynard had now cast a forlorn look towards home at last. There was now a disposition to give him his life, but what could we do ? Old Driver was at his brush; His Majesty’s Guards could not have saved him. Thus ended a chase during which were traversed about twenty-five Irish miles (making thirty English) of the fairest portion of Lower Ormond. In running in Messrs. Fitzgibbon and Henry Westenra took a neat sporting leap. A gentleman of jockey weight, who rode well thro’ the chase, wishing no doubt to show us the length of his neck, craned at it, swore it was the ugliest place in Europe, and that a flock of sheep might be regularly hid in it. There was a very numerous field at finding. During this most desperate fox-chase, George Jackson rode as usual with the hounds, as did Lord Rossmore, Colonel Eyre, Messrs. Fitzgibbon, Henry Westenra, Richard Faulkener, and Burton Persse all through.’

I have copied the account verbatim, but I cannot help thinking that second huntsman should be second horseman—or whip.

There was no harder man to hounds in Meath than the present Lord Rossmore, grandson of the hero of this tale, till he hurt his leg, and the late Burton Persse, who for some thirty seasons was Master of ‘ the Blazers,’ was a grandson of the ‘ Knight of the Bath ‘ referred to here. So it seems old Horace was a good judge, and that ‘Fortes creantur fortibus et bonis.‘

Home

Top of Pg.

|

King Leopold Butcher of the Congo For the somewhat startling suggestion in the heading of this interview, the missionary interviewed is in no way responsible. The credit of it, or, if you like, the discredit, belongs entirely to the editor of the Review, who, without dogmatism, wishes to pose the question as [...] Read more →

Click here to view Period Furniture Guide Home Top of Pg. Read more →

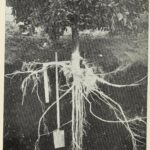

What follows is a chapter from Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s 1852 treatise on terrarium gardening. ON THE NATURAL CONDITIONS OF PLANTS. To enter into any lengthened detail on the all-important subject of the Natural Conditions of Plants would occupy far too much space; yet to pass it by without special notice, [...] Read more →

Click here to view a copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Click on the blue button to download a free copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Arban's - 11.8MB For trumpet players wishing to practice daily using an iPad, simply click [...] Read more →

Aw, the good old days, meet in the coffee shop with a few friends, click open the Zippo, inhale a glorious nosegay of lighter fluid, fresh roasted coffee and a Marlboro cigarette…. A Meta-analysis of Coffee Drinking, Cigarette Smoking, and the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease We conducted a [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Here, where these low lush meadows lie, We wandered in the summer weather, When earth and air and arching sky, Blazed grandly, goldenly together. And oft, in that same summertime, We sought and roamed these self-same meadows, When evening brought the curfew chime, And peopled field and fold with shadows. I mind me [...] Read more →

A rhetorical question? Genuine concern? In this essay we are examining another form of matter otherwise known as national literary matters, the three most important of which being the Matter of Rome, Matter of France, and the Matter of England. Our focus shall be on the Matter of England or [...] Read more →

“Saint John’s Gate, Clerkenwell, the main gateway to the Priory of Saint John of Jerusalem,” black and white photograph by the British photographer Henry Dixon, 1880. The church was founded in the 12th century by Jordan de Briset, a Norman knight. Prior Docwra completed the gatehouse shown in this photograph in 1504. The gateway [...] Read more →

Home Top of [...] Read more →

ON THE ORIGIN OF SPECIES BY MEANS OF NATURAL SELECTION, OR THE PRESERVATION OF FAVOURED RACES IN THE STRUGGLE FOR LIFE. BY CHARLES DARWIN, M.A., FELLOW OF THE ROYAL, GEOLOGICAL, LINNÆAN, ETC., SOCIETIES ; AUTHOR OF ‘JOURNAL OF RESEARCHES DURING H.M.S. BEAGLE’S [...] Read more →

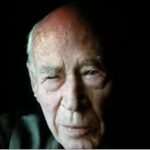

Dr. David Starkey, the UK’s premiere historian, speaks to the modern and fleeting notion of “cancel culture”. Starkey’s brilliance is unparalleled and it has become quite obvious to the world’s remaining Western scholars willing to stand on intellectual integrity that a few so-called “Woke Intellectuals” most certainly cannot undermine [...] Read more →

Looking to spice up your dinner? Let’s hop along and cook some roo. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

? The Band: Miles Davis (trumpet), Wayne Shorter (sax), Herbie Hancock (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Tony Williams (drums) Home Top of Pg. Read more →

First Pineapple Grown in England Click here to read an excellent article on the history of pineapple growing in the UK. Should one be interested in serious mass scale production, click here for scientific resources. Growing pineapples in the UK. The video below demonstrates how to grow pineapples in Florida. [...] Read more →

For years in the West African nation of Ghana medicine men have used a root and leaves from a plant called nibima(Cryptolepis sanguinolenta) to kill the Plasmodium parasite transmitted through a female mosquito’s bite that is the root cause of malaria. A thousand miles away in India, a similar(same) plant [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

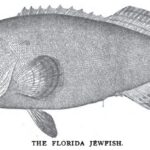

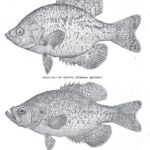

Nov. 5. 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 371-372 The Black Grouper or Jewfish. New Smyrna, Fla., Oct. 21.—Editor Forest and Stream: It is not generally known that the fish commonly called jewfish. warsaw and black grouper are frequently caught at the New Smyrna bridge [...] Read more →

Photo by Greg O’Beirne Home Top of Pg. Read more →

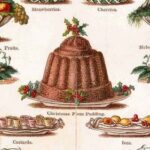

Traditional British Christmas Pudding Recipe by Pen Vogler from the Charles Dickens Museum Ingredients 85 grams all purpose flour pinch of salt 170 grams Beef Suet 140 grams brown sugar tsp. mixed spice, allspice, cinnamon, cloves, &c 170 grams bread crumbs 170 grams raisins 170 grams currants 55 grams cut mixed peel Gram to [...] Read more →

July 9, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 25 Some Notes on American Ship-Worms. [Read before the American Fishes Congress at Tampa.] While we wish to preserve and protect most of the products of our waters, these creatures we would gladly obliterate from the realm of living things. For [...] Read more →

Today I shall share a bit of market wisdom that will be hard to swallow for some Rolex owners, especially if they bought their Submariner at the top of the magical Covid Watch Bubble that has now collapsed. History often repeats itself, even in the stock market, but when [...] Read more →

Photo Caption: The Marquis of Zetland, KC, PC – otherwise known as Lawrence Dundas Son of: John Charles Dundas and: Margaret Matilda Talbot born: Friday 16 August 1844 died: Monday 11 March 1929 at Aske Hall Occupation: M.P. for Richmond Viceroy of Ireland Vice Lord Lieutenant of North Yorkshire Lord – in – Waiting [...] Read more →

An angler with a costly pole Surmounted with a silver reel, Carven in quaint poetic scroll- Jointed and tipped with finest steel— With yellow flies, Whose scarlet eyes And jasper wings are fair to see, Hies to the stream Whose bubbles beam Down murmuring eddies wild and free. And casts the line with sportsman’s [...] Read more →

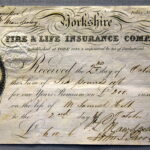

Life insurance certificate issued by the Yorkshire Fire & Life Insurance Company to Samuel Holt, Liverpool, England, 1851. On display at the British Museum in London. Donated by the ifs School of Finance. Photo by Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg) From How to Make Money; and How to Keep it, Or, Capital and Labor [...] Read more →

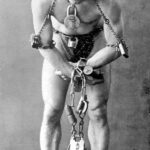

The magician delighted in exposing spiritualists as con men and frauds. By EDMUND WILSON June 24, 1925 Houdini is a short strong stocky man with small feet and a very large head. Seen from the stage, his figure, with its short legs and its pugilist’s proportions, is less impressive than at close [...] Read more →

Chipping a Turpentine Tree DISTILLING TURPENTINE One of the Most Important Industries of the State of Georgia Injuring the Magnificent Trees Spirits, Resin, Tar, Pitch, and Crude Turpentine all from the Long Leaved Pine – “Naval Stores” So Called. Dublin, Ga., May 8. – One of the most important industries [...] Read more →

The Racing Knockabout Gosling. Gosling was the winning yacht of 1897 in one of the best racing classes now existing in this country, the Roston knockabout class. The origin of this class dates back about six years, when Carl, a small keel cutter, was built for C. H. [...] Read more →

Welcome to Country House Essays. Enjoy. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

PAINTER-WORK, in the building trade. When work is painted one or both of two distinct ends is achieved, namely the preservation and the coloration of the material painted. The compounds used for painting—taking the word as meaning a thin protective or decorative coat—are very numerous, including oil-paint of many kinds, distemper, whitewash, [...] Read more →

King Arthur, Legends, Myths & Maidens is a massive book of Arthurian legends. This limited edition paperback was just released on Barnes and Noble at a price of $139.00. Although is may seem a bit on the high side, it may prove to be well worth its price as there are only [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

From Conquest of the Tropics by Frederick Upham Adams Chapter VI – Birth of the United Fruit Company Only those who have lived in the tropic and are familiar with the hazards which confront the cultivation and marketing of its fruits can readily understand [...] Read more →

Armorial tablet of the Stewarts – Falkland Palace Fife, Scotland. The Stewart Kings – King James I & VI to Charles II Six video playlist on the Kings of England: Home Top of Pg. Read more →

FRIED SQUIRREL & BISCUIT GRAVY 3-4 Young Squirrels, dressed and cleaned 1 tsp. Morton Salt or to taste 1 tsp. McCormick Black Pepper or to taste 1 Cup Martha White All Purpose Flour 1 Cup Hog Lard – Preferably fresh from hog killing, or barbecue table Cut up three to [...] Read more →

Fed Chariman William McChesney Martin – 1952-1970 [Editor note: This response in my mind is quite hilarious…and to the point…who the heck would want to give up 6% interest year after year after year after year? ] You HAVE ASKED that I appear before you today in connection with your consideration [...] Read more →

Roger Scruton – Why Beauty Matters (2009) from Mirza Akdeniz on Vimeo. Click here for another site on which to view this video. Sadly, Sir Roger Scruton passed away a few days ago—January 12th, 2020. Heaven has gained a great philosopher. Home Top of [...] Read more →

From Dr. Marvel’s 1929 book entitled Hoodoo for the Common Man, we find his infamous Hoochie Coochie Hex. What follows is a verbatim transcription of the text: The Hoochie Coochie Hex should not be used in conjunction with any other Hexes. This can lead to [...] Read more →

From Fores’s Sporting Notes and Sketches, A Quarterly Magazine Descriptive of British, Indian, Colonial, and Foreign Sport with Thirty Two Full Page Illustrations Volume 10 1893, London; Mssrs. Fores Piccadilly W. 1893, All Rights Reserved. GLIMPSES OF THE CHASE, Ireland a Hundred Years Ago. By ‘Triviator.’ FOX-HUNTING has, like Racing, [...] Read more →

Roger Scruton by Peter Helm This is one of those videos that the so-called intellectual left would rather not be seen by the general public as it makes a laughing stock of the idiots running the artworld, a multi-billion dollar business. https://archive.org/details/why-beauty-matters-roger-scruton or Click here to watch [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Guarea guidonia Recipe 5 Per Cent Alcohol 8-24 Grain – Heroin Hydrochloride 120 Minims – Tincture Euphorbia Pilulifera 120 Minims – Syrup Wild Lettuce 40 Minims – Tincture Cocillana 24 Minims – Syrup Squill Compound 8 Gram – Ca(s)ecarin (P, D, & Co.) 8-100 Grain Menthol Dose – One-half to one fluidrams (2 to [...] Read more →

H.F. Leonard was an instructor in wrestling at the New York Athletic Club. Katsukum Higashi was an instructor in Jujitsu. “I say with emphasis and without qualification that I have been unable to find anything in jujitsu which is not known to Western wrestling. So far as I can see, [...] Read more →

. Home Top of [...] Read more →

New York Stock Exchange Floor September 26,1963 The Specialist as a member of a stock exchange has two functions.’ He must execute orders which other members of an exchange may leave with him when the current market price is away from the price of the orders. By executing these orders on behalf [...] Read more →

Photo by Rebecca Humann Texas Tea Recipe 2 oz Cuervo Gold Tequila Home Top of [...] Read more →

Biograph Theater, where John Dillinger was gunned down by the FBI on July 22, 1934 The Great Depression was on—highway based crime was rampant, the gangsters dressed as well as the bankers they robbed, and and Henry Ford’s big beautiful V8 sedan was the getaway car of choice for both wheelman and [...] Read more →

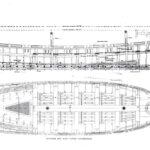

Dec. 24, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 513-514 The Standard Navy Boats. Above we find, The accompanying illustrations show further details of the standard navy boats, the lines of which appeared last week. In all of these boats, as stated previously, the quality of speed has been given [...] Read more →

Book Conservators, Mitchell Building, State Library of New South Wales, 29.10.1943, Pix Magazine The following is taken verbatim from a document that appeared several years ago in the Maine State Archives. It seems to have been removed from their website. I happened to have made a physical copy of it at the [...] Read more →

VITRUVIUS The Ten Books on Architecture TRANSLATED By MORRIS HICKY MORGAN, PH.D., LL.D. LATE PROFESSOR OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN HARVARD UNIVERSITY WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND ORIGINAL DESINGS PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF HERBERT LANGFORD WARREN, A.M. NELSON ROBINSON JR. PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE IN HARVARD [...] Read more →

The Hunt Saboteur is a national disgrace barking out loud, black mask on her face get those dogs off, get them off she did yell until a swift kick from me mare her voice it did quell and sent the Hunt Saboteur scurrying up vale to the full cry of hounds drowning out her [...] Read more →

Over the years I have observed a decline in manners amongst young men as a general principle and though there is not one particular thing that may be asserted as the causal reason for this, one might speculate… Self-awareness and being aware of one’s surroundings in social interactions [...] Read more →

Dutch artist Herman de Vries – Photo taken by son Vince The two videos below of Herman de Vries at work at the Venice Bienalle 2015 are quite inspiring. So inspiring in fact that I moved into a cave for two weeks and wrote Shakespearean tragedy with charcoal. Filled with great joy [...] Read more →

The following research discussion is from a study funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health entitled: Boschniakia rossica prevents the carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in rat. It may be of interest to heavy drinkers. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Stoke Park Pavillions Stoke Park Pavilions, UK, view from A405 Road. photo by Wikipedia user Cj1340 From Wikipedia: Stoke Park – the original house Stoke park was the first English country house to display a Palladian plan: a central house with balancing pavilions linked by colonnades or [...] Read more →

Kenilworth Abbey Fields – Photo by David Hunt Click here to read Kenilworth by Sir Walter Scott Click here to view Kenilworth Notes Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Robert W. Service (b.1874, d.1958) There are strange things done in the midnight sun By the men who moil for gold; The Arctic trails have their secret tales That would make your blood run cold; The Northern Lights have seen queer sights, But the queerest they ever did see Was that night [...] Read more →

KING ARTHUR AND HIS KNIGHTS On the decline of the Roman power, about five centuries after Christ, the countries of Northern Europe were left almost destitute of a national government. Numerous chiefs, more or less powerful, held local sway, as far as each could enforce his dominion, and occasionally those [...] Read more →

To Clean Watch Chains. Gold or silver watch chains can be cleaned with a very excellent result, no matter whether they may be matt or polished, by laying them for a few seconds in pure aqua ammonia; they are then rinsed in alcohol, and finally. shaken in clean sawdust, free from sand. [...] Read more →

THE HATHA YOGA PRADIPIKA Translated into English by PANCHAM SINH Panini Office, Allahabad [1914] INTRODUCTION. There exists at present a good deal of misconception with regard to the practices of the Haṭha Yoga. People easily believe in the stories told by those who themselves [...] Read more →

Filed under Miscellaneous. The Jubbulpore School of Industry is so thriving that the pupils, 800 in number, are obliged to work till ten o’clock at night to complete their orders; this they do most cheerfully. They are all Thugs, or the children of Thugs, and the hands which now ply [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Take the large blue figs when pretty ripe, and steep them in white wine, having made some slits in them, that they may swell and gather in the substance of the wine. Then slice some other figs and let them simmer over a fire in water until they are reduced [...] Read more →

Click here to visit Lil’ Lost Lou and purchase a copy of her latest album. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to read the Swiss National Bank’s Chronicle of Monetary Events. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The following cure was found written on a front flyleaf in an 1811 3rd Ed. copy of The Sportsman’s Guide or Sportsman’s Companion: Containing Every Possible Instruction for the Juvenille Shooter, Together with Information Necessary for the Experienced Sportsman by B. Thomas. Transcript: Vaccinate your dogs when young [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A la Russie, aux ânes et aux autres – by Chagall – 1911 Marc Chagall is one of the most forged artists on the planet. Mark Rothko fakes also abound. According to available news reports, the art market is littered with forgeries of their work. Some are even thought to be [...] Read more →

IT requires a far search to gather up examples of furniture really representative in this kind, and thus to gain a point of view for a prospect into the more ideal where furniture no longer is bought to look expensively useless in a boudoir, but serves everyday and commonplace need, such as [...] Read more →

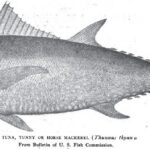

July, 16, l898 Forest and Stream Pg. 48 Tuna and Tarpon. New York, July 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: If any angler still denies the justice of my claim, as made in my article in your issue of July 2, that “the tuna is the grandest game [...] Read more →

” Here’s many a year to you ! Sportsmen who’ve ridden life straight. Here’s all good cheer to you ! Luck to you early and late. Here’s to the best of you ! You with the blood and the nerve. Here’s to the rest of you ! What of a weak moment’s swerve ? [...] Read more →

Baking is a very similar process to roasting: the two often do duty for one another. As in all other methods of cookery, the surrounding air may be several degrees hotter than boiling water, but the food is no appreciably hotter until it has lost water by evaporation, after which it may [...] Read more →

Click here to access the world’s most powerful Import/Export Research Database on the Planet. With this search engine one is able to access U.S. Customs and other government data showing suppliers for any type of company in the United States. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The Ardabil Carpet – Made in the town of Ardabil in north-west Iran, the burial place of Shaykh Safi al-Din Ardabili, who died in 1334. The Shaykh was a Sufi leader, ancestor of Shah Ismail, founder of the Safavid dynasty (1501-1722). While the exact origins of the carpet are unclear, it’s believed to have [...] Read more →

BEEF JERKY Preparation. Slice 5 pounds lean beef (flank steak or similar cut) into strips 1/8 to 1/4 inch thick, 1 to 2 inches wide, and 4 to 12 inches long. Cut with grain of meat; remove the fat. Lay out in a single layer on a smooth clean surface (use [...] Read more →

German made shotguns by Krieghoff, founded in 1886. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to view more great Italian recipes. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Half a league, half a league, Half a league onward, All in the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. “Forward, the Light Brigade! Charge for the guns!” he said. Into the valley of Death Rode the six hundred. Home Top of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

It is unnecessary to point out that low-grade fruit may often be used to advantage in the preparation of vinegar. This has always been true in the case of apples and may be true with other fruit, especially grapes. The use of grapes for wine making is an outlet which [...] Read more →

The Chicago portion of the The Great Train Story at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago. by Interiority Home Top of Pg. Read more →

THE answer to the question, What is fortune has never been, and probably never will be, satisfactorily made. What may be a fortune for one bears but small proportion to the colossal possessions of another. The scores or hundreds of thousands admired and envied as a fortune in most of our communities [...] Read more →

Gilbert Stewart – Sir Joshua Reynolds SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS‘ WORKING COLOURS, WITH THE ORDER IN WHICH THEY WERE ARRANGED ON HIS PALLETTE. “For painting the flesh, black, blue black, white, lake, carmine, orpiment, yellow ochre, ultramarine, and varnish. “To lay the [...] Read more →

Chen Lin, Water fowl, in Cahill, James. Ge jiang shan se (Hills Beyond a River: Chinese Painting of the Yuan Dynasty, 1279-1368, Taiwan edition). Taipei: Shitou chubanshe fen youxian gongsi, 1994. pl. 4:13, p. 180. Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei. scroll, light colors on paper, 35.7 x 47.5 cm Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Vintage woodcut illustration of a Eel This dish is a favorite in Northern Europe, from the British Isles to Sweden. Clean and skin the eels and cut them into pieces about 3/4-inch thick. Wash and drain the pieces, then dredge in fine salt and allow to stand from 30 [...] Read more →

Blackbeard’s Jolly Roger If you’re looking for that most refreshing of summertime beverages for sipping out on the back patio or perhaps as a last drink before walking the plank, let me recommend my Blunderbuss Mai Tai. I picked up the basics to this recipe over thirty years ago when holed up [...] Read more →

Country House Essays has returned after a good long summer holiday. More essays soon. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

STORE MANAGEMENT—THE SHIRK. THE shirk is a well-known specimen of the genus homo. His habitat is offices, stores, business establishments of all kinds. His habits are familiar to us, but a few words on the subject will not be amiss. The shirk usually displays activity when the boss is around, [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The arsenicals (compounds which contain the heavy metal element arsenic, As) have a long history of use in man – with both benevolent and malevolent intent. The name ‘arsenic’ is derived from the Greek word ‘arsenikon’ which means ‘potent'”. As early as 2000 BC, arsenic trioxide, obtained from smelting copper, was used [...] Read more →

NAPOLEON’S PHARMACISTS. Of the making of books about Napoleon there is no end, and the centenary of his death (May 5) is not likely to pass without adding to the number, but a volume on Napoleon”s pharmacists still awaits treatment by the student in this field of historical research. There [...] Read more →

Aug. 13, 1898 Forest and Stream, Pg. 125 Game Bag and Gun. Indian Modes of Hunting. III.—Foxes. The fox as a rule is a most wily animal, and numerous are the stories of his cunning toward the Indian hunter with his steel traps. Read more →

Quite possibly, the most agonizing decision being made by Baby Boomers across the nation these days is what to do with all that vintage Hi-fi equipment and boxes full of classic rock and roll cassettes and 8-Tracks. I faced this dilemma head-on this past summer as I definitely wanted in [...] Read more →

“The Leda, in the Colonna palace, by Correggio, is dead-coloured white and black, with ultramarine in the shadow ; and over that is scumbled, thinly and smooth, a warmer tint,—I believe caput mortuum. The lights are mellow ; the shadows blueish, but mellow. The picture is painted on panel, in [...] Read more →

The arsenicals (compounds which contain the heavy metal element arsenic, As) have a long history of use in man – with both benevolent and malevolent intent. The name ‘arsenic’ is derived from the Greek word ‘arsenikon’ which means ‘potent'”. As early as 2000 BC, arsenic trioxide, obtained from smelting copper, was used [...] Read more →

July 2, 1898 Forest and Stream, Fresh-Water Angling. No. IX.—The Two Crappies. BY FRED MATHER. Fishing In Tree Tops. Here a short rod, say 8ft., is long enough, and the line should not be much longer than the rod. A reel is not [...] Read more →

Twinings London – photo by Elisa.rolle Is the tea in your cup genuine? The fact is, had one been living in the early 19th Century, one might occasionally encounter a counterfeit cup of tea. Food adulterations to include added poisonings and suspect substitutions were a common problem in Europe at [...] Read more →

Gary Kravit is an airline pilot and artist. He also owns and operates https://theultimatetaboret.com. You may view Gary’s art at https://garrykravitart.blogspot.com/ Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A Lecture Delivered at the Guildhall, March 2, 1853 by Rev. H.M. Scarth, M.A., Rector of Bathwick. To understand the ancient history of the country in which we live, to know something of the arts and manners of the people who have preceded us, to ascertain what we owe [...] Read more →

Hudson Bay: Trappers, 1892. N’Talking Musquash.’ Fur Trappers Of The Hudson’S Bay Company Talking By A Fire. Engraving After A Drawing By Frederic Remington, 1892. Indian Modes of Hunting. IV.—Musquash. In Canada and the United States, the killing of the little animal known under the several names of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Edwin Austin Abbey. King Lear, Act I, Scene I (Cordelia’s Farewell) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dates: 1897-1898 Dimensions: Height: 137.8 cm (54.25 in.), Width: 323.2 cm (127.24 in.) Medium: Painting – oil on canvas Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A Real Soda Jerk FORMULAS FROM VARIOUS SOURCES. Pineapple Frappe. Water, 1 gallon; sugar 2 pounds of water. 61/2 pints, and simple syrup. 2 1/2 pints; 2 pints of pineapple stock or 1 pint of pineapple stock and 1 pint of grated pineapple juice of 6 lemons. Mix, [...] Read more →

The greatest cause of failure in vinegar making is carelessness on the part of the operator. Intelligent separation should be made of the process into its various steps from the beginning to end. PRESSING THE JUICE The apples should be clean and ripe. If not clean, undesirable fermentations [...] Read more →

Silverfish damage to book – photo by Micha L. Rieser The beauty of hunting silverfish is that they are not the most clever of creatures in the insect kingdom. Simply take a small clean glass jar and wrap it in masking tape. The masking tape gives the silverfish something to [...] Read more →

Cleremont Club 44 Berkeley Square, London Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Cabildo circa 1936 The Cabildo houses a rare copy of Audubon’s Bird’s of America, a book now valued at $10 million+. Should one desire to visit the Cabildo, click here to gain free entry with a lowcost New Orleans Pass. Home Top of [...] Read more →

And now for the transformation of Gray Gardens Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Bess of Harwick Four times the nuptial bed she warm’d, And every time so well perform’d, That when death spoil’d each husband’s billing, He left the widow every shilling. Fond was the dame, but not dejected; Five stately mansions she erected With more than royal pomp, to vary The prison of her captive When [...] Read more →

AB Bookman’s 1948 Guide to Describing Conditions: As New is self-explanatory. It means that the book is in the state that it should have been in when it left the publisher. This is the equivalent of Mint condition in numismatics. Fine (F or FN) is As New but allowing for the normal effects of [...] Read more →

Dried Norwegian Salt Cod Fried fish cakes are sold rather widely in delicatessens and at prepared food counters of department stores in the Atlantic coastal area. This product has possibilities for other sections of the country. Ingredients: Home Top of [...] Read more →

by John Partridge,drawing,1825 From the work of Sir Charles Lock Eastlake entitled Materials for a history of oil painting, (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1846), we learn the following: The effect of oil at certain temperatures, in penetrating “the minute pores of the amber” (as Hoffman elsewhere writes), is still more [...] Read more →

Sept. 3, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg. 188-189 How to Distinguish Fishes. BY FRED MATHER. The average angler knows by sight all the fish which he captures, but ask him to describe one and he is puzzled, and will get off on the color of the fish, which is [...] Read more →

WIPO HQ Geneva UNITED STATES PLANT VARIETY PROTECTION ACT TITLE I – PLANT VARIETY PROTECTION OFFICE Chapter Section 1. Organization and Publications . 1 2. Legal Provisions as to the Plant Variety Protection Office . 21 3. Plant Variety Protection Fees . 31 CHAPTER 1.-ORGANIZATION AND PUBLICATIONS Section [...] Read more →

Liquorice, the roots of Glycirrhiza Glabra, a perennial plant, a native of the south of Europe, but cultivated to some extent in England, particularly at Mitcham, in Surrey. Its root, which is its only valuable part, is long, fibrous, of a yellow colour, and when fresh, very juicy. [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

INTRODUCTION The idea of compiling this little volume occurred to me while on a visit to some friends at their summer home in a quaint New England village. The little town had once been a thriving seaport, but now consisted of hardly more than a dozen old-fashioned Colonial houses facing [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Absolutely Brilliant! And as I am quite certain you will become a fan, there’s more! Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Video courtesy of Imperial War Museums, UK Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Paul Thorpe, Brighton, U.K. The YouTube watch collecting world is rather tight-knit and small, but growing, as watches became a highly coveted commodity during the recent world-wide pandemic and fueled an explosion of online watch channels. There is one name many know, The Time Piece Gentleman. This name for me [...] Read more →

William Wyggeston’s chantry house, built around 1511, in Leicester: The building housed two priests, who served at a chantry chapel in the nearby St Mary de Castro church. It was sold as a private dwelling after the dissolution of the chantries. A Privately Built Chapel Chantry, chapel, generally within [...] Read more →

Salmon and Sturgeon Caviar – Photo by Thor Salmon caviar was originated about 1910 by a fisherman in the Maritime Provinces of Siberia, and the preparation is a modification of the sturgeon caviar method (Cobb 1919). Salomon caviar has found a good market in the U.S.S.R. and other European countries where it [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The following recipes form the most popular items in a nine-course dinner program: BIRD’S NEST SOUP Soak one pound bird’s nest in cold water overnight. Drain the cold water and cook in boiling water. Drain again. Do this twice. Clean the bird’s nest. Be sure [...] Read more →

Oh Glorious England, verdant fields and wandering canals… In this wonderful series of videos, the CountryHouseGent takes the viewer along as he chugs up and down the many canals crisscrossing England in his classic Narrowboat. There is nothing like a free man charting his own destiny. Read more →

If ever it could be said that there is such a thing as miracle healing soil, Ivan Sanderson said it best in his 1965 book entitled Ivan Sanderson’s Book of Great Jungles. Sanderson grew up with a natural inclination towards adventure and learning. He hailed from Scotland but spent much [...] Read more →

Hebborn Piranesi Before meeting with an untimely death at the hand of an unknown assassin in Rome on January 11th, 1996, master forger Eric Hebborn put down on paper a wealth of knowledge about the art of forgery. In a book published posthumously in 1997, titled The Art Forger’s Handbook, Hebborn suggests [...] Read more →

Early Texas photo of Tarpon catch – Not necessarily the one mentioned below… July 2, 1898. Forest and Stream Pg.10 Texas Tarpon. Tarpon, Texas.—Mr. W. B. Leach, of Palestine, Texas, caught at Aransas Pass Islet, on June 14, the largest tarpon on record here taken with rod and reel. The [...] Read more →

1 garlic clove, cut in half 1 8-oz. pkg. Philadelphia Brand Cream Cheese 3 tablespoons clam broth 1 7-to 7 1/2-oz. can minced clams, drained Home Top of [...] Read more →

Wine Making Grapes are the world’s leading fruit crop and the eighth most important food crop in the world, exceeded only by the principal cereals and starchytubers. Though substantial quantities are used for fresh fruit, raisins, juice and preserves, most of the world’s annual production of about 60 million [...] Read more →

The Effect of Magnetic Fields on Wound Healing Experimental Study and Review of the Literature Steven L. Henry, MD, Matthew J. Concannon, MD, and Gloria J. Yee, MD Division of Plastic Surgery, University of Missouri Hospital & Clinics, Columbia, MO Published July 25, 2008 Objective: Magnets [...] Read more →

Add the following ingredients to a four or six quart crock pot, salt & pepper to taste keeping in mind that salt pork is just that, cover with water and cook on high till it boils, then cut back to low for four or five hours. A slow cooker works well, I [...] Read more →

The low level of work stoppages of recent years also attests to concern about job security. Testimony of Chairman Alan Greenspan The Federal Reserve’s semiannual monetary policy report Before the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, U.S. Senate February 26, 1997 Iappreciate the opportunity to appear before this Committee [...] Read more →

Charles Dickens wrote much more than novels. In fact he turned out several very interesting dictionaries to include one of London, one of Paris and one on London’s long meandering river Thames. Click here to read a copy of the Dictionary of the Thames. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

John Atkinson Grimshaw – Glasgow Saturday Night Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Add 3 quarts clover blossoms* to 4 quarts of boiling water removed from heat at point of boil. Let stand for three days. At the end of the third day, drain the juice into another container leaving the blossoms. Add three quarts of fresh water and the peel of one lemon to the blossoms [...] Read more →

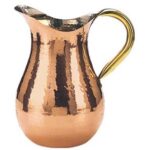

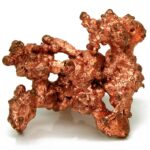

Are you considering purchasing a copper water pitcher for storing drinking water but have questions about the effects on your health? The following study may help jump-start your research. Storing Drinking-water in Copper pots Kills Contaminating Diarrhoeagenic Bacteria ABSTRACT Microbially-unsafe water is [...] Read more →

WITCHCRAFT, SORCERY, MAGIC AND OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL PHENOMENA AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS ON MILITARY AND PARAMILITARY OPERATIONS IN THE CONGO This report has been prepared in response to a query posed by ODCS/OPS, Department of the Army, regarding the purported use of witchcraft, sorcery, and magic by insurgent elements in the Republic [...] Read more →

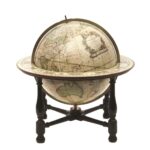

A terrestial globe on which the tracts and discoveries are laid down from the accurate observations made by Capts Cook, Furneux, Phipps, published 1782 / globe by John Newton ; cartography by William Palmer, held by the State Library of New South Wales The British Library, using sophisticated filming equipment and software, [...] Read more →

|

Add 3 quarts clover blossoms* to 4 quarts of boiling water removed from heat at point of boil. Let stand for three days. At the end of the third day, drain the juice into another container leaving the blossoms. Add three quarts of fresh water and the peel of one lemon to the blossoms [...] Read more →

Traditional British Christmas Pudding Recipe by Pen Vogler from the Charles Dickens Museum Ingredients 85 grams all purpose flour pinch of salt 170 grams Beef Suet 140 grams brown sugar tsp. mixed spice, allspice, cinnamon, cloves, &c 170 grams bread crumbs 170 grams raisins 170 grams currants 55 grams cut mixed peel Gram to [...] Read more →

Blackbeard’s Jolly Roger If you’re looking for that most refreshing of summertime beverages for sipping out on the back patio or perhaps as a last drink before walking the plank, let me recommend my Blunderbuss Mai Tai. I picked up the basics to this recipe over thirty years ago when holed up [...] Read more →

EIGHTEEN GALLONS is here give as a STANDARD for all the following Recipes, it being the most convenient size cask to Families. See A General Process for Making Wine If, however, only half the quantity of Wine is to be made, it is but to divide the portions of [...] Read more →

Reprint from The Sportsman’s Cabinet and Town and Country Magazine, Vol I. Dec. 1832, Pg. 94-95 To the Editor of the Cabinet. SIR, Possessing that anxious feeling so common among shooters on the near approach of the 12th of August, I honestly confess I was not able [...] Read more →

“Saint John’s Gate, Clerkenwell, the main gateway to the Priory of Saint John of Jerusalem,” black and white photograph by the British photographer Henry Dixon, 1880. The church was founded in the 12th century by Jordan de Briset, a Norman knight. Prior Docwra completed the gatehouse shown in this photograph in 1504. The gateway [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Edwin Austin Abbey. King Lear, Act I, Scene I (Cordelia’s Farewell) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Dates: 1897-1898 Dimensions: Height: 137.8 cm (54.25 in.), Width: 323.2 cm (127.24 in.) Medium: Painting – oil on canvas Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Are you considering purchasing a copper water pitcher for storing drinking water but have questions about the effects on your health? The following study may help jump-start your research. Storing Drinking-water in Copper pots Kills Contaminating Diarrhoeagenic Bacteria ABSTRACT Microbially-unsafe water is [...] Read more →

Hunters at Work This is a recipe I created from scratch by trial and error. (Note: This recipe contains no eggs, refined white flour or white sugar.) 2 Cups Whole Wheat Flour – As unprocessed as you can find it 3 Cups of Raw Oatmeal 1 Cup of [...] Read more →

It is unnecessary to point out that low-grade fruit may often be used to advantage in the preparation of vinegar. This has always been true in the case of apples and may be true with other fruit, especially grapes. The use of grapes for wine making is an outlet which [...] Read more →

Click here to view a copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Click on the blue button to download a free copy of Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Cornet Arban's - 11.8MB For trumpet players wishing to practice daily using an iPad, simply click [...] Read more →

Click here to visit Ovation Guitars Ovation Patent Drawing 1975 Click here to read a copy of the 1975 Patent for the Ovation Guitar Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Cleaner for Gilt Frames. Calcium hypochlorite…………..7 oz. Sodium bicarbonate……………7 oz. Sodium chloride………………. 2 oz. Distilled water…………………12 oz. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

? The Band: Miles Davis (trumpet), Wayne Shorter (sax), Herbie Hancock (piano), Ron Carter (bass), Tony Williams (drums) Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Hudson Bay: Trappers, 1892. N’Talking Musquash.’ Fur Trappers Of The Hudson’S Bay Company Talking By A Fire. Engraving After A Drawing By Frederic Remington, 1892. Indian Modes of Hunting. IV.—Musquash. In Canada and the United States, the killing of the little animal known under the several names of [...] Read more →

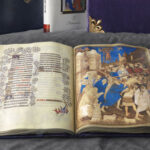

Buying a book for a serious collector with refined tastes can be a daunting task. However, there is one company that publishes some of the finest reproduction books in the world, books that most collectors wouldn’t mind having in their collection no matter their general preference or specialty. Read more →

John Keats Four Seasons fill the measure of the year; There are four seasons in the mind of man: He has his lusty spring, when fancy clear Takes in all beauty with an easy span; He has his Summer, when luxuriously Spring’s honied cud of youthful thoughts he loves To ruminate, and by such [...] Read more →

The Diamond Empire Home Top of [...] Read more →

Today I shall share a bit of market wisdom that will be hard to swallow for some Rolex owners, especially if they bought their Submariner at the top of the magical Covid Watch Bubble that has now collapsed. History often repeats itself, even in the stock market, but when [...] Read more →

The magician delighted in exposing spiritualists as con men and frauds. By EDMUND WILSON June 24, 1925 Houdini is a short strong stocky man with small feet and a very large head. Seen from the stage, his figure, with its short legs and its pugilist’s proportions, is less impressive than at close [...] Read more →

From Allen’s Indian Mail, December 3rd, 1851 BOMBAY. MUSULMAN FANATICISM. On the evening of November 15th, the little village of Mahim was the scene of a murder, perhaps the most determined which has ever stained the annals of Bombay. Three men were massacred in cold blood, in a house used [...] Read more →

Artisans world-wide spend a fortune on commercial brand oil-based gold leaf sizing. The most popular brands include Luco, Dux, and L.A. Gold Leaf. Pricing for quart size containers range from $35 to $55 depending upon retailer pricing. Fast drying sizing sets up in 2-4 hours depending upon environmental conditions, humidity [...] Read more →

To Choose Poultry. When fresh, the eyes should be clear and not sunken, the feet limp and pliable, stiff dry feet being a sure indication that the bird has not been recently killed; the flesh should be firm and thick and if the bird is plucked there should be no [...] Read more →

And now for the transformation of Gray Gardens Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Oct. 22, 1898 Forest and Stream Pg. 324 An Alaskan Moose Head. Tacoma, Washington; Oct. 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: In your issue of March 6, 1897, you showed cut of a pair of moose horns belonging to me that spread 73 1/2 in.— at that time [...] Read more →

Tom Oates, aka Nabokov at en.wikipedia No two commercial tuna salads are prepared by exactly the same formula, but they do not show the wide variety characteristic of herring salad. The recipe given here is typical. It is offered, however, only as a guide. The same recipe with minor variations to suit [...] Read more →

German made shotguns by Krieghoff, founded in 1886. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to access the Internet Archive of old Popular Mechanics Magazines – 1902-2016 Click here to view old Popular Mechanics Magazine Covers Home Top of Pg. Read more →

INTRODUCTION The idea of compiling this little volume occurred to me while on a visit to some friends at their summer home in a quaint New England village. The little town had once been a thriving seaport, but now consisted of hardly more than a dozen old-fashioned Colonial houses facing [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY INROMATION FROM FOREIGN DOCUMENT OR RADIO BROADCASTS COUNTRY: Non-Orbit SUBJECT: Military – Air – Scientific – Aeronautics HOW PUBLISHED: Newspapers WHERE PUBLISHED: As indicated DATE PUBLISHED: 12 Dec 1953 – 12 Jan 1954 LANGUAGE: Various SOURCE: As indicated REPORT NO. 00-W-30357 DATE OF INFORMATION: 1953-1954 DATE DIST. 27 [...] Read more →

Roger Scruton by Peter Helm This is one of those videos that the so-called intellectual left would rather not be seen by the general public as it makes a laughing stock of the idiots running the artworld, a multi-billion dollar business. https://archive.org/details/why-beauty-matters-roger-scruton or Click here to watch [...] Read more →

Charles Dickens wrote much more than novels. In fact he turned out several very interesting dictionaries to include one of London, one of Paris and one on London’s long meandering river Thames. Click here to read a copy of the Dictionary of the Thames. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to view more great Italian recipes. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

As reported in the The Colac Herald on Friday July 17, 1903 Pg. 8 under Art Appreciation as a reprint from the Westminster Gazette ART APPRECIATION IN THE COMMONS. The appreciation of art as well as of history which is entertained by the average member of the [...] Read more →

The greatest cause of failure in vinegar making is carelessness on the part of the operator. Intelligent separation should be made of the process into its various steps from the beginning to end. PRESSING THE JUICE The apples should be clean and ripe. If not clean, undesirable fermentations [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

VITRUVIUS The Ten Books on Architecture TRANSLATED By MORRIS HICKY MORGAN, PH.D., LL.D. LATE PROFESSOR OF CLASSICAL PHILOLOGY IN HARVARD UNIVERSITY WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND ORIGINAL DESINGS PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF HERBERT LANGFORD WARREN, A.M. NELSON ROBINSON JR. PROFESSOR OF ARCHITECTURE IN HARVARD [...] Read more →

The following recipes form the most popular items in a nine-course dinner program: BIRD’S NEST SOUP Soak one pound bird’s nest in cold water overnight. Drain the cold water and cook in boiling water. Drain again. Do this twice. Clean the bird’s nest. Be sure [...] Read more →

It was a strange assignment. I picked up the telegram from desk and read it a third time. NEW YORK, N.Y., MAY 9, 1949 HAVE BEEN INVESTIGATING FLYING SAUCER MYSTERY. FIRST TIP HINTED GIGANTIC HOAX TO COVER UP OFFICIAL SECRET. BELIEVE IT MAY HAVE BEEN PLANTED TO HIDE [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Oh Glorious England, verdant fields and wandering canals… In this wonderful series of videos, the CountryHouseGent takes the viewer along as he chugs up and down the many canals crisscrossing England in his classic Narrowboat. There is nothing like a free man charting his own destiny. Read more →

July, 16, l898 Forest and Stream Pg. 48 Tuna and Tarpon. New York, July 1.—Editor Forest and Stream: If any angler still denies the justice of my claim, as made in my article in your issue of July 2, that “the tuna is the grandest game [...] Read more →

Click here to learn more about The Tallis Scholars Home Top of Pg. Read more →

H.F. Leonard was an instructor in wrestling at the New York Athletic Club. Katsukum Higashi was an instructor in Jujitsu. “I say with emphasis and without qualification that I have been unable to find anything in jujitsu which is not known to Western wrestling. So far as I can see, [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Reprint from the Sportsman Cabinet and Town & Country Magazine, Vol.1, Number 1, November 1832. MR. Editor, Will you allow me to inquire, through the medium of your pages, the correct meaning of the term thorough-bred fox-hound? I am very well aware, that the expression is in common [...] Read more →

The arsenicals (compounds which contain the heavy metal element arsenic, As) have a long history of use in man – with both benevolent and malevolent intent. The name ‘arsenic’ is derived from the Greek word ‘arsenikon’ which means ‘potent'”. As early as 2000 BC, arsenic trioxide, obtained from smelting copper, was used [...] Read more →

The element copper effectively kills viruses and bacteria. Therefore it would reason and I will assert and not only assert but lay claim to the patents for copper mesh stints to be inserted in the arteries of patients presenting with severe cases of Covid-19 with a slow release dosage of [...] Read more →

To learn more about Julian McDonnell, film director, click here. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

The downloadable audio clip is of FDR’s Second Fireside Chat recorded on May 7th, 1933. FDR 2nd Fireside Chat - May 7, 1933 - 18.5MB The transcript that follows is my corrected version of the transcript that is found The American Presidency Project website that was created [...] Read more →

The first published illustration of Nicotiana tabacum by Pena and De L’Obel, 1570–1571 (shrpium adversana nova: London). Tobacco can be used for medicinal purposes, however, the ongoing American war on smoking has all but obscured this important aspect of ancient plant. Tobacco is considered to be an indigenous plant of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A rhetorical question? Genuine concern? In this essay we are examining another form of matter otherwise known as national literary matters, the three most important of which being the Matter of Rome, Matter of France, and the Matter of England. Our focus shall be on the Matter of England or [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Click here to read the full text of the Hunting Act – 2004 Home Top of Pg. Read more →

A la Russie, aux ânes et aux autres – by Chagall – 1911 Marc Chagall is one of the most forged artists on the planet. Mark Rothko fakes also abound. According to available news reports, the art market is littered with forgeries of their work. Some are even thought to be [...] Read more →

Click here to access the world’s most powerful Import/Export Research Database on the Planet. With this search engine one is able to access U.S. Customs and other government data showing suppliers for any type of company in the United States. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

From the classic British Movie, The Shooting Party, a 1985 British drama film directed by Alan Bridges based on Isabel Colegate’s 9th novel of the same name published in 1980 we find a scene set in the billiards parlor whereupon the host of the weekend shooting party Sir Randolph Nettleby walks in [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

VHF Marifoon Sailor RT144, by S.J. de Waard RADIO INFORMATION FOR BOATERS Effective 01 August, 2013, the U. S. Coast Guard terminated its radio guard of the international voice distress, safety and calling frequency 2182 kHz and the international digital selective calling (DSC) distress and safety frequency 2187.5 kHz. Additionally, [...] Read more →

PEACH BRANDY 2 gallons + 3 quarts boiled water 3 qts. peaches, extremely ripe 3 lemons, cut into sections 2 sm. pkgs. yeast 10 lbs. sugar 4 lbs. dark raisins Place peaches, lemons and sugar in crock. Dissolve yeast in water (must NOT be to hot). Stir thoroughly. Stir daily for 7 days. Keep [...] Read more →

Video courtesy of Imperial War Museums, UK Home Top of Pg. Read more →

WIPO HQ Geneva UNITED STATES PLANT VARIETY PROTECTION ACT TITLE I – PLANT VARIETY PROTECTION OFFICE Chapter Section 1. Organization and Publications . 1 2. Legal Provisions as to the Plant Variety Protection Office . 21 3. Plant Variety Protection Fees . 31 CHAPTER 1.-ORGANIZATION AND PUBLICATIONS Section [...] Read more →

H. M. Scarth, Rector of Wrington By the death of Mr. Scarth on the 5th of April, at Tangier, where he had gone for his health’s sake, the familiar form of an old and much valued Member of the Institute has passed away. Harry Mengden Scarth was bron at Staindrop in Durham, [...] Read more →

Reprint from The Pitfalls of Speculation by Thomas Gibson 1906 Ed. THE PUBLIC ATTITUDE TOWARD SPECULATION THE public attitude toward speculation is generally hostile. Even those who venture frequently are prone to speak discouragingly of speculative possibilities, and to point warningly to the fact that an overwhelming majority [...] Read more →

Mortlake Tapestries at Chatsworth House Click here to learn more about the Mortlake Tapestries of Chatsworth The Mortlake Tapestries were founded by Sir Francis Crane. From the Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 13 Crane, Francis by William Prideaux Courtney CRANE, Sir FRANCIS (d. [...] Read more →

Muscadine Jelly 6 cups muscadine grape juice 6 cups sugar 1 box Kraft Sure Gel or Ball Fruit Jell Home Top of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Looking to spice up your dinner? Let’s hop along and cook some roo. Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Filed under Miscellaneous. The Jubbulpore School of Industry is so thriving that the pupils, 800 in number, are obliged to work till ten o’clock at night to complete their orders; this they do most cheerfully. They are all Thugs, or the children of Thugs, and the hands which now ply [...] Read more →

Snipe shooting-Epistle on snipe shooting, from Ned Copper Cap, Esq., to George Trigger-George Trigger’s reply to Ned Copper Cap-Black partridge. —— “Si sine amore jocisque Nil est jucundum, vivas in &more jooisque.” -Horace. “If nothing appears to you delightful without love and sports, then live in sporta and [...] Read more →

Aug. 13, 1898 Forest and Stream, Pg. 125 Game Bag and Gun. Indian Modes of Hunting. III.—Foxes. The fox as a rule is a most wily animal, and numerous are the stories of his cunning toward the Indian hunter with his steel traps. Read more →

Country House Christmas Pudding Ingredients 1 cup Christian Bros Brandy ½ cup Myer’s Dark Rum ½ cup Jim Beam Whiskey 1 cup currants 1 cup sultana raisins 1 cup pitted prunes finely chopped 1 med. apple peeled and grated ½ cup chopped dried apricots ½ cup candied orange peel finely chopped 1 ¼ cup [...] Read more →

A Real Soda Jerk FORMULAS FROM VARIOUS SOURCES. Pineapple Frappe. Water, 1 gallon; sugar 2 pounds of water. 61/2 pints, and simple syrup. 2 1/2 pints; 2 pints of pineapple stock or 1 pint of pineapple stock and 1 pint of grated pineapple juice of 6 lemons. Mix, [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Como dome facade – Pliny the Elder – Photo by Wolfgang Sauber Work in Progress… THE VARNISHES. Every substance may be considered as a varnish, which, when applied to the surface of a solid body, gives it a permanent lustre. Drying oil, thickened by exposure to the sun’s heat or [...] Read more →

Dried Norwegian Salt Cod Fried fish cakes are sold rather widely in delicatessens and at prepared food counters of department stores in the Atlantic coastal area. This product has possibilities for other sections of the country. Ingredients: Home Top of [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Resolution adapted at the New Orleans Convention of the American Institute of Banking, October 9, 1919: “Ours is an educational association organized for the benefit of the banking fraternity of the country and within our membership may be found on an equal basis both employees and employers; [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Gold Home Top of Pg. Read more →

What follows is a chapter from Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward’s 1852 treatise on terrarium gardening. ON THE NATURAL CONDITIONS OF PLANTS. To enter into any lengthened detail on the all-important subject of the Natural Conditions of Plants would occupy far too much space; yet to pass it by without special notice, [...] Read more →

Vintage woodcut illustration of a Eel This dish is a favorite in Northern Europe, from the British Isles to Sweden. Clean and skin the eels and cut them into pieces about 3/4-inch thick. Wash and drain the pieces, then dredge in fine salt and allow to stand from 30 [...] Read more →

Chipping a Turpentine Tree DISTILLING TURPENTINE One of the Most Important Industries of the State of Georgia Injuring the Magnificent Trees Spirits, Resin, Tar, Pitch, and Crude Turpentine all from the Long Leaved Pine – “Naval Stores” So Called. Dublin, Ga., May 8. – One of the most important industries [...] Read more →

The following recipes are from a small booklet entitled 500 Delicious Salads that was published for the Culinary Arts Institute in 1940 by Consolidated Book Publishers, Inc. 153 N. Michigan Ave., Chicago, Ill. If you have been looking for a way to lighten up your salads and be free of [...] Read more →

The Clermont Club Reprint from London Bisnow/UK At £23M, its sale is not the biggest property deal in the world. But the Clermont Club casino in Berkeley Square in London could lay claim to being the most significant address in modern finance — it is where the concept of what is today [...] Read more →

Citrus Fruit Culture THE PRINCIPAL fruit and nut trees grown commercially in the United States (except figs, tung, and filberts) are grown as varieties or clonal lines propagated on rootstocks. Almost all the rootstocks are grown from seed. The resulting seedlings then are either budded or grafted with propagating wood [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

Armorial tablet of the Stewarts – Falkland Palace Fife, Scotland. The Stewart Kings – King James I & VI to Charles II Six video playlist on the Kings of England: Home Top of Pg. Read more →

From Dr. Marvel’s 1929 book entitled Hoodoo for the Common Man, we find his infamous Hoochie Coochie Hex. What follows is a verbatim transcription of the text: The Hoochie Coochie Hex should not be used in conjunction with any other Hexes. This can lead to [...] Read more →

” Here’s many a year to you ! Sportsmen who’ve ridden life straight. Here’s all good cheer to you ! Luck to you early and late. Here’s to the best of you ! You with the blood and the nerve. Here’s to the rest of you ! What of a weak moment’s swerve ? [...] Read more →

Add the following ingredients to a four or six quart crock pot, salt & pepper to taste keeping in mind that salt pork is just that, cover with water and cook on high till it boils, then cut back to low for four or five hours. A slow cooker works well, I [...] Read more →

Home Top of Pg. Read more →

BLACKBERRY WINE 5 gallons of blackberries 5 pound bag of sugar Fill a pair of empty five gallon buckets half way with hot soapy water and a ¼ cup of vinegar. Wash thoroughly and rinse. Fill one bucket with two and one half gallons of blackberries and crush with [...] Read more →